This story originally ran in the November 6, 2009 edition of The Guide

BY JAY STRUTH

Bob Middleton of Killarney already knew he wanted to fly and fight for his country while he was finishing high school, just as World War II was getting underway. On January 7, 1942, at the age of 19, he enlisted in the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) in Winnipeg.

“I went into Winnipeg in January and I just happened to hit a class that was going down to Lachine, Quebec,” said Middleton. “There were 44 of us that went to Lachine, which was just opening up as a manning depot, and when we got there 30 of us were picked to go into a precision squad. The other poor buggers went out to the east coast for guard duty and had to walk around a fence for a bit. We got the best of that deal.”

While at the newly opened Lachine depot, three squads of 30 men each spent days practicing drills and leveling land for a runway.

“When we weren’t practicing we were shoveling and raking this land and leveling it off so they could put a tarmac on it,” said Middleton. “Half the day was drills and the other half was work.”

Next, Middleton’s Manitoba squad was posted to Victoriaville, Quebec where they took their ground-training course.

“When we finished our course we all put in what we wanted to do, not necessarily that we’d get to do it, but my idea was to be a pilot,” he said. “Even before I started I wanted to be a pilot. But they decided whether you did it or not.”

After taking Elementary Flight Training School (EFTS) in Victoriaville, an order came through in August that the air force needed five training pilots to go to Virden, Manitoba.

“So all the fellas who were going to be pilots went to the chapel, and we drew straws, and I drew one of the right ones,” remembered Middleton. “So myself, and four other guys came to Virden and took our EFTS flying Tiger Moths, which was our first training aircraft. We were there until October and then we went to Dauphin and flew Cessna Cranes. In February 1943, we got our wings.”

In March, Middleton and another trainee pilot and one of the instructors were sent to Pennfield Ridge in New Brunswick where they started training on Venturas.

“Venturas had 1800 hp in each motor, so that was quite the experience,” he recalled. “That’s where we got our crew, the four of us. Everybody that had that course hoped they were going over to England to convert onto Mitchell bombers, B-25s. And we did. We went over to England and used the B-25s to bomb. We arrived in Liverpool, the first receiving depot, on Canada Day.”

In August, Middleton’s crew was posted to No. 13 Operational Training Unit and flew B-25 Mitchells.

“We were supposed to continue flying Mitchells but they had more pilots than they needed at that time,” said Middleton. “So after about five weeks holiday, when we all were broke in London and couldn’t do anything because we were broke, we went back and we joined 292 Squadron.”

In January 1944 they were sent to No. 1665 HCU to fly Stirling aircraft. There, two new members were added to their crew because of the bigger size of the plane.

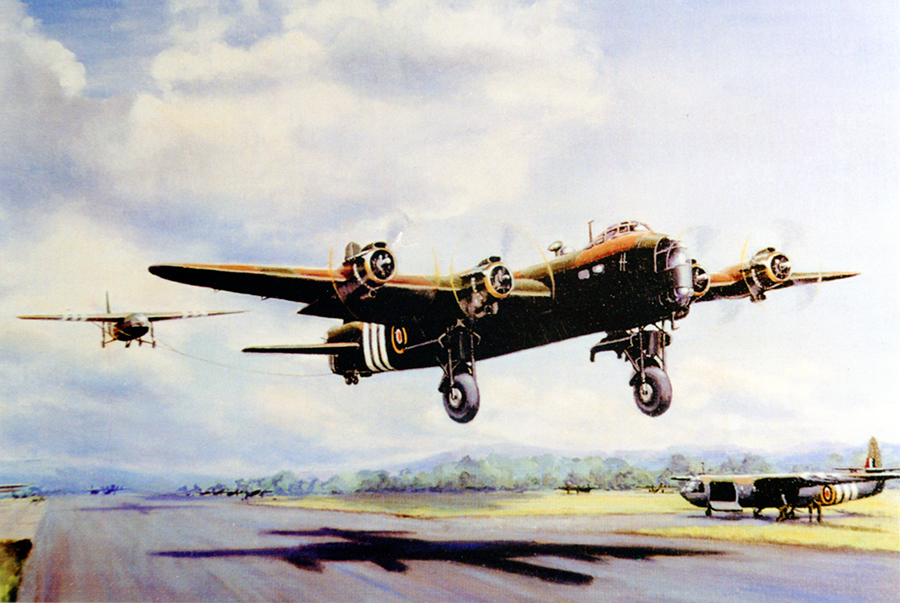

“Then, the big shots decided that they were going to rush out and help invade France, so they formed a 38 Group out of 10 squadrons,” said Middleton. “We were going to fly Stirling aircraft, which was a four engine aircraft. We were to pull the Horsa gliders and train Horsa glider pilots, and also train parachuters.”

Middleton’s crew was posted to No. 38 Group RAF, No. 190 Squadron in January 1944, and soon began carrying out missions. Their main duties were to drop supplies and paratroopers to the underground in France, the Low Countries and Norway, along with training Horsa glider pilots and paratroopers.

“We started delivering supplies at night to the underground in France who needed help to blow up railroad stations and stuff like that,” he said. “So we dropped supplies and paratroopers in the moonlight period. There had to be moonlight because we had to map read into the field that we were to drop in. A lot of the paratroopers we dropped were radio operators so they could talk to England anytime they needed to, and they told us where to drop the supplies.”

Middleton’s crew participated in the airborne landings at Normandy, Arnhem and the Rhine Crossing.

“We were the first to go in on the invasion at Normandy,” he said. “We dropped our paratroopers and we were back home in England by 1 o’clock in the morning (on D-Day, June 6, 1944). There were quite a few squadrons, because they were trying to do it all at once. The first night that’s what we did.”

As the battle raged on during the next couple of days they dropped supplies to the troops on the ground, including ammunition and guns or whatever else was needed.

“Our job, mostly, was to put the paratroopers and the supplies on the bridges or near the bridges so they would have control of them when the army came in,” said Middleton. “They held the bridges until the Canadian army and the British army got in there.”

Middleton said their squadron lost a couple of aircraft doing the drops in Normandy, but it was during the September invasion of Arnhem that they took their biggest hit, losing 12 or 13 aircraft within a matter of a week.

“We were one of the ones that got hit,” he said. “We had a button that we could push if a fire started in any one of our four motors and we were able to get the fire out, but we lost that motor. We got hit on the inside right motor and practically blew it right off the aircraft, so it was no good, but the propeller kept running. And that means that if they ran out of oil they seize up and then the blades fly off and they had a tendency to hit the tail controls, so we were lucky it didn’t.

One of Middleton’s friends, who he got his wings with back in Canada, was hit about the same time.

“He wasn’t any farther than 100 feet off my wing, and they got his gas tank,” remembered Middleton. “We saw three parachutes come out and we found out later that two of them had got out okay but the third one was dead when he got to the ground. The other two, one went to the hospital and the other one was taken prisoner of war (POW). The three of them got out but the rest of them didn’t and the plane just went down. My friend was the pilot, and he died.”

Middleton managed to bring his wounded aircraft home, but at a much slower pace.

“In fact, they gave up on us,” he remembered. “We were two hours late getting back to the station. Then we landed but we didn’t have any brakes, but we were on a long runway because we pulled gliders so we ended up alright.”

For his efforts, Middleton was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC) and his tail gunner, Bill Angus, received the Oak Leaves medal.

Bob and his crew also took part in some bombing runs, although they were not part of their regular duties. Toward the end of the war they became a transport squadron, flying fuel and supplies through Europe and bringing back POWs.

“At the end of the war, the allies were short of gas when they got as far as Holland and Belgium, so they filled us up with a bunch of jerry cans and we flew these jerry cans over filled with gas, and then we got some of the prisoners of war out and we brought them back to England,” he recalled. “The POWs that were over in Hong Kong and through that area were pretty bad. But most of our fellas that we picked up, they had a lot of bugs on them and stuff, but they weren’t in too bad of shape. Mind you they were starving to death, but so were all the German people in the camps where they were prisoners. Nobody had any food and they were depending an awful lot on Red Cross parcels. The Red Cross could go into any one of the countries.”

Middleton’s tour of duty ended in May 1945, and he was discharged from the RCAF in Winnipeg that November after a brief stint with No. 244 RCAF Squadron in England. He returned home to Killarney where he was employed at Anderson’s retail clothing store.

Bob and his wife, Dolores (Dot), were married on September 30, 1946 and they had two children, Karen and Jeffery. In 1957 they took over Anderson’s store and in 1967 they built the General Store building on Broadway Avenue, where Bob’s Clothing was housed until the couple’s retirement in 1986.

“As far as my DFC medal was concerned, it should include all of us, but the pilot gets it,” he said as he displayed his medal and the short write up accompanying it. “I was the captain of the aircraft, so I flew the aircraft and the rest of them told me what to do. We were all in the tour together, and we were all in the aircraft when it happened and everything else. So it’s really a crew thing, but the captain gets the medal.”

The write up that accompanies his DFC award reads, “Flying Officer Middleton has completed a tour of operational duty which included 17 supply dropping missions to France, the Low Countries in Norway, and participation in the airborne landings at Normandy, Arnhem and the Rhine Crossing. Throughout as pilot and captain of aircraft he has displayed coolness and determination in the face of difficulties…At all times Flying Officer Middleton’s skill, cheerfulness and imperturbability have inspired the members of his crew with confidence.”

“You don’t flap,” he said. “If you flap, you’re dead. But when it comes down to it, we were lucky. We were very lucky.”

DISTINGUISHED FLYING CROSS – Late WWII vet Bob Middleton of Killarney (pictured back in 2009) holds up the Distinguished Flying Cross he was awarded for bringing his wounded plane safely back to base during the invasion of Arnhem, among other successful missions. He’s kept a variety of pictures and other memorabilia from his war days, including a photo of his old Stirling aircraft called “Z” Zebra.

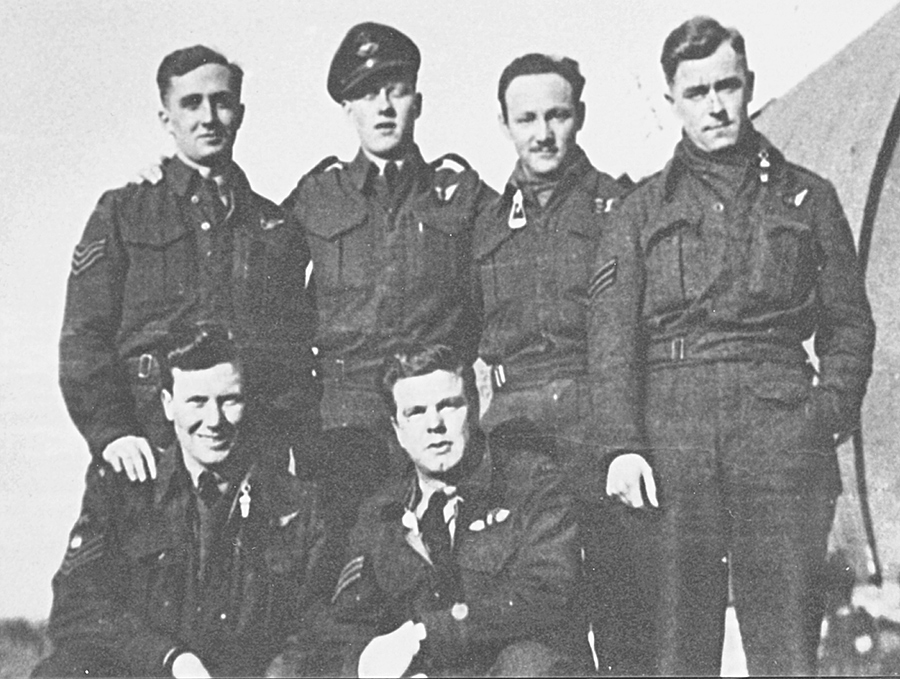

FLIGHT CREW – Bob Middleton (front, centre) or Mid as he was called by his friends, captained his crew of Cretney (clockwise from Mid), Beck, Bosley, Angus and Drury during their tour in WWII.

GLIDING – The Short Stirling pulling a British Horsa Glider. The Horsa Glider had a crew of two pilots and could carry 25 to 30 paratroopers; or 15 paratroopers, one jeep, and one trailer; or six paratroopers, one jeep, and one anti-tank gun.